By: Abhishek Singh

Introduction: When Tradition Meets the Global Runway

In late 2024, an unexpected storm brewed—not in Parliament or the courtroom—but across social media timelines. Fashion enthusiasts in India were quick to point out that an opulent sandal from the Italian luxury house Prada looked strikingly familiar. With minimalist stitching, a single-piece sole, and the signature toe loop, it bore a strong resemblance to the Kolhapuri chappal—the iconic handcrafted footwear deeply rooted in the cultural fabric of Maharashtra and Karnataka.

The only glaring difference? The price tag. While a pair of authentic Kolhapuris may cost a few hundred rupees in India, Prada’s version was being retailed for over ₹80,000.

Beyond the meme-worthy contrast lay a serious question that India’s artisans and policymakers must now confront: Can our Geographical Indication (GI) system genuinely protect traditional designs from being diluted—or worse, exploited—by global corporations?

Kolhapuri Chappals: A Heritage Etched in Leather

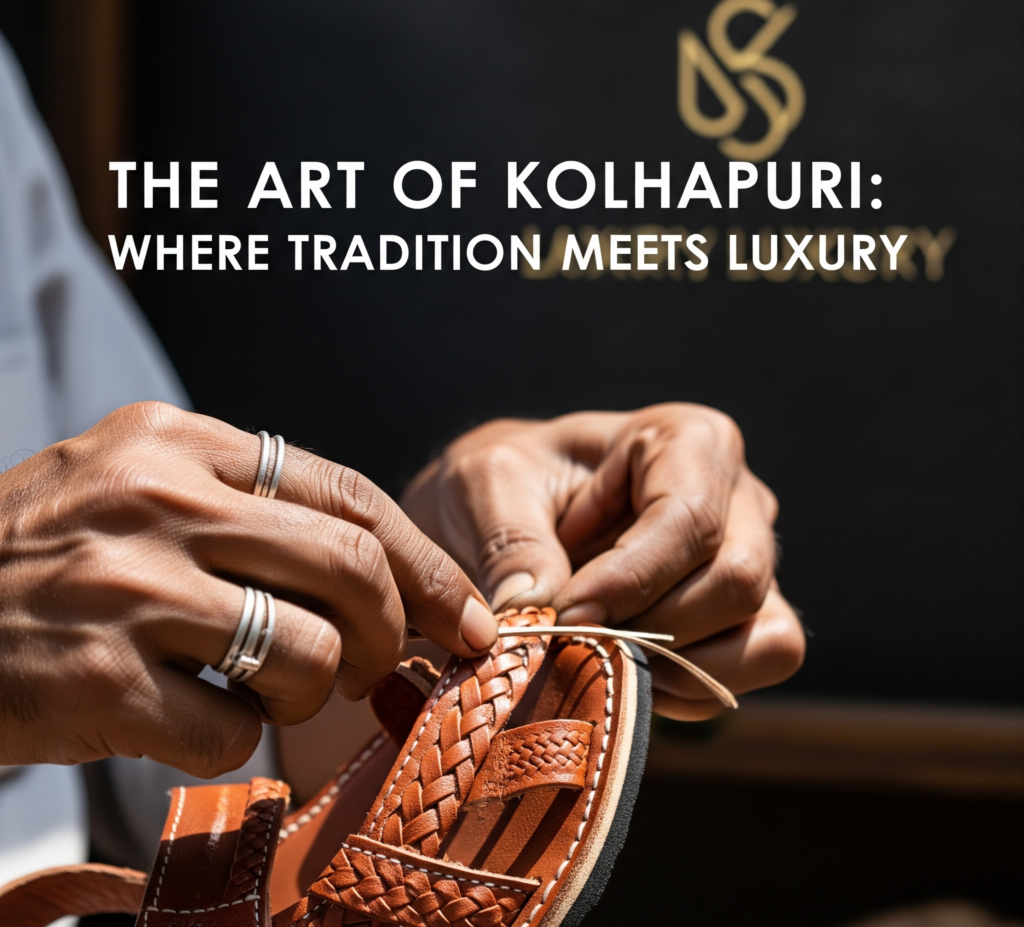

The Kolhapuri chappal is no ordinary sandal. With intricate braiding, meticulous stitching, and leather processing techniques passed down through generations, this footwear represents more than mere craftsmanship—it is a living tradition. Artisans in Kolhapur, Athani, and nearby regions often learn this trade within families, beginning as early as adolescence.

In 2019, these chappals were granted GI status under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, jointly by Maharashtra and Karnataka. The tag acknowledged:

- The geographical uniqueness of the product

- The traditional craftsmanship involved

- The need to protect artisans’ rights in a globalizing market

Yet, as the Prada case shows, recognition without enforcement is like a chappal without a sole—symbolic but not functional.

The Prada Sandal Controversy: Inspiration or Appropriation?

In the world of luxury fashion, drawing from cultural motifs is nothing new. From Japanese kimonos on French runways to African tribal prints in Western boutiques, inspiration flows freely. However, when this inspiration turns into imitation—without acknowledgment, collaboration, or compensation—it raises the specter of cultural appropriation.

Prada’s design, though not named “Kolhapuri,” carried unmistakable visual markers. Yet nowhere in its product description did it mention India, Kolhapur, or traditional leather artisans. There was no effort to collaborate with Indian communities, nor was there any channel to share profits with the originators of the design.

This wasn’t just an artistic oversight—it was a missed ethical obligation, further highlighted when Kolhapuri artisans publicly demanded recognition and governmental intervention after Milan Fashion Week, emphasizing their GI-protected craft had been showcased without a mention of its origin.

Legal Framework: What a GI Tag Can and Cannot Do

Understanding Geographical Indications

The GI Act, 1999, defines a geographical indication as a sign used on goods that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or reputation due to that origin. While the name “Kolhapuri” is protected, the design features of the sandal are not.

Key Limitations of the Current GI Regime

- No protection of appearance or aesthetic design unless separately registered under the Designs Act, 2000

- No extraterritorial application—meaning, the law doesn’t apply outside India unless mirrored in a bilateral treaty or foreign court

- Enforcement must be initiated by registered proprietors or authorized users, often small cooperatives with limited legal budgets

This gap makes it exceedingly difficult to prevent multinational corporations from replicating Indian designs—so long as they don’t use the protected name.

Case Laws and Legal Precedents

Tea Board of India v. ITC Ltd (2011)

One major case often cited in GI-related matters is Tea Board of India v. ITC Ltd (2011). Here, the use of the name “Darjeeling Lounge” for a hotel bar was challenged by the Tea Board, which owns the GI for “Darjeeling Tea.” The Calcutta High Court ruled that there was no infringement because the term was not used for tea or related products.

This case highlights how GI laws focus heavily on product-name association. Just copying the style or essence of a GI-protected item is usually not enough to constitute legal violation.

Amar Nath Sehgal v. Union of India

Another important precedent is the Amar Nath Sehgal v. Union of India case, where the Delhi High Court ruled on the misuse of cultural expressions in public spaces. Although not directly about GI, the judgment reinforced the need to respect the origins and rights associated with cultural creations, recognizing moral rights of artists and communities. This case has been influential in discussions about cultural appropriation and respect for heritage in India.

International Precedent: Basmati Rice GI Dispute

Internationally, the Basmati Rice GI dispute between India and Pakistan offers insight into cross-border GI enforcement challenges. The Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) in India upheld India’s exclusive right over “Basmati” as a GI, reinforcing the principle that a geographical indication must be strictly linked to origin and production methods. This case underscores how nations struggle to protect traditional products in global markets.

These precedents underscore a crucial point: misuse of design alone—without name or origin reference—is rarely sufficient under GI law. The financial and legal asymmetry between rural artisan cooperatives and global fashion houses is therefore stark.

Cultural Appropriation: A Legal Blind Spot

The Challenge of Traditional Cultural Expressions

The Prada incident highlights a deeper, systemic issue: existing IP laws are ill-equipped to handle cultural appropriation.

Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs)—like folk songs, motifs, designs, and rituals—are often community-owned and collectively evolved. Yet current IP laws, rooted in Euro-American individualist frameworks, do not recognize this communal authorship.

The GRATK Treaty: A New Hope

Efforts by WIPO to draft a treaty on the protection of TCEs culminated in the GRATK Treaty, adopted in May 2024, which for the first time addresses traditional knowledge and expressions in a formal international IP instrument.

International Gaps and Asymmetries

The Disparity in Protection

In contrast, France’s Champagne, Italy’s Parma ham, and Scotland’s whisky enjoy strong international safeguards—often backed by trade diplomacy. Their producers have the institutional and legal capacity to fight counterfeits worldwide.

But can Kolhapuri artisan cooperatives, often operating at the brink of subsistence, hire international IP attorneys to take on Prada in Italy? The answer is obvious—and disheartening.

Future Trade Agreements

India’s recent India-EU Free Trade Agreement negotiations have seen GI protection tabled as a key issue. If successful, such treaties could allow Kolhapuri artisans to enjoy reciprocal protection in European markets.

What Needs to Change: Legal and Ethical Pathways Forward

Legal Solutions

- Design GI Integration: India could amend its GI law to enable automatic design protection for GI-certified goods, especially when visual aesthetics are integral

- Mandatory GI registration in key markets: Particularly the EU and US, where luxury knock-offs likely surface

- Community IP frameworks: Adapt laws to allow for collective ownership and representation, especially for artisan clusters

Ethical Responsibilities for Brands

Brands like Prada must lead with conscience, not just commerce:

- Collaborate with artisan cooperatives

- Adopt fair trade certifications

- Share credit and profits when designs borrow from Indigenous traditions

We’ve seen hopeful models: Dior’s collaboration with Indian weavers, Hermès’ partnerships with Ghanaian leatherworkers, and UNESCO-backed artisan co-branding in Peru. These examples show ethical fashion can be both profitable and culturally respectful.

IPR and GI: Are Traditional Crafts Truly Protected?

The Broader IPR Ecosystem

Geographical Indications (GIs) form one component of the broader Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) ecosystem. Unlike trademarks or patents, which are typically owned by individuals or corporations, GIs represent collective ownership by a community. However, this distinction creates challenges when traditional designs or crafts are replicated outside their place of origin.

Gaps in Current Protection

While GI protection in India is governed by the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, it is product-specific—meaning it safeguards the name (“Kolhapuri”), the origin (Kolhapur, Maharashtra and parts of Karnataka), and the method of production. But it does not offer broader protection under other branches of IPR, such as:

- Design Law: Unless artisans also register the visual design under the Designs Act, 2000, others may legally mimic it abroad

- Copyright Law: Protects original artistic works, but most traditional designs do not qualify as they are not by a single “author”

- Trademark Law: Cannot prevent appropriation unless the community has registered a specific logo or mark

The Need for Sui Generis Protection

In essence, while GIs are recognized under IPR, they function in isolation, leaving traditional artisans vulnerable when:

- Designs are copied but names are altered (as in the Prada sandal)

- Communities lack the legal capacity or knowledge to register under multiple regimes

- Global IP systems favor individual innovation over collective heritage

Legal scholars such as Prof. N.S. Gopalakrishnan have repeatedly called for a sui generis regime—a unique law that goes beyond current IPR categories and recognizes cultural and design expressions as protected community rights.

International Models for Inspiration

India can also draw inspiration from models like:

- Peru’s collective trademarks for Quechua textiles

- Ethiopia’s IP licensing of coffee brands like Sidamo and Yirgacheffe

These examples show that when IPR frameworks are broadened to include cultural justice, they can play a transformative role in empowering indigenous and artisan communities.

Conclusion: Preserving the Sole and the Soul

The Kolhapuri-Prada controversy underscores a stark truth: legal frameworks often lag behind moral imperatives. A GI tag can help preserve a name, but it cannot yet protect the essence—the style, the craft, the soul—of cultural products in a global marketplace.

India’s legal system must now evolve into a tool for cultural justice. Protecting Kolhapuris is not just about footwear—it’s about respecting generations of artisans who weave identity and dignity into every stitch.

To truly protect the sole, we must first protect the soul—and that means giving India’s artisans not just rights on paper, but a seat at the global table.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a Geographical Indication (GI) tag?

A Geographical Indication (GI) tag is a sign used on products that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or reputation due to that origin. Under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, it protects the name and origin of traditional products but does not automatically protect their design or appearance.

When did Kolhapuri chappals receive GI protection?

Kolhapuri chappals were granted GI status in July 2019 under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, jointly by Maharashtra and Karnataka states. The GI tag covers four districts each from Maharashtra (Kolhapur, Sangli, Satara, and Solapur) and Karnataka (Belgaum, Dharwad, Bagalkot, and Bijapur).

Who owns the GI tag for Kolhapuri chappals?

The GI tag for Kolhapuri chappals is officially owned by two Maharashtra government-run corporations: Sant Rohidas Leather Industries & Charmakar Development Corporation Limited (LIDCOM) and Dr. Babu Jagjivanram Leather Industries Development Corporation Limited (LIDKAR) from Karnataka, facilitated by Central Leather Research Institute, Chennai.

Can a GI tag prevent international brands from copying traditional designs?

Currently, GI tags have limited effectiveness in preventing design copying by international brands. They protect the name and origin but not the visual design unless separately registered under the Designs Act, 2000. Additionally, GI protection has no extraterritorial application unless mirrored in bilateral treaties or foreign courts.

What was the main issue with Prada’s sandal controversy?

The main issue was that Prada’s Spring/Summer 2026 collection sandal bore striking resemblance to traditional Kolhapuri chappals with similar stitching, sole design, and toe loop, but was sold for over ₹80,000 without any acknowledgment of its Indian origins or collaboration with traditional artisans. Following public pressure, Prada acknowledged the Indian inspiration.

What is cultural appropriation in the context of fashion?

Cultural appropriation in fashion occurs when brands adopt traditional designs, motifs, or styles from indigenous or traditional communities without acknowledgment, collaboration, or compensation to the originators. It becomes problematic when inspiration turns into imitation without ethical consideration, often resulting in economic harm to original creators.

What are some famous examples of cultural appropriation in fashion?

Notable cases include ASOS selling Indian tikka as “Chandelier Hair Clip,” Victoria’s Secret using Native American feathered headdresses, KTZ copying Inuit parka designs, Urban Outfitters’ Navajo-themed collection, and Carolina Herrera using Mexican indigenous patterns without acknowledgment.

What are Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs)?

Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs) are folk songs, motifs, designs, and rituals that are community-owned and collectively evolved over generations. Current IP laws, based on individualist frameworks, often fail to recognize this communal authorship.

What is the GRATK Treaty?

The GRATK Treaty, adopted by WIPO in May 2024, is the first formal international IP instrument that addresses traditional knowledge and expressions, offering new hope for protecting community-owned cultural heritage.

How long does a GI tag last?

A GI tag is initially valid for 10 years from the date of registration and can be renewed indefinitely as long as the product continues to meet specified standards and maintains its association with the geographical area of origin.

Who can apply for a GI tag in India?

Applications can be made by associations of persons, producers, organizations, or government authorities that represent the interests of the producers. Individual producers cannot directly apply – they must be part of an association or represented by an organization.

What is the process to get a GI tag in India?

The process involves: 1) Filing application with the Geographical Indications Registry in Chennai, 2) Preliminary examination for deficiencies, 3) Expert evaluation of the statement of case, 4) Public notification and opposition period, 5) Final registration if no valid opposition exists. The process typically takes 1-3 years.

How much does it cost to get a GI tag?

The application fee for GI registration in India varies based on the type of applicant. Small producers and associations typically pay lower fees compared to larger organizations. Additional costs include documentation, legal assistance, and renewal fees every 10 years.

How do other countries protect their traditional products internationally?

Countries like France (Champagne), Italy (Parma ham), and Scotland (whisky) enjoy strong international safeguards backed by trade diplomacy and have institutional capacity to fight counterfeits worldwide through established legal frameworks and international treaties.

What legal changes are needed to better protect traditional crafts?

Key legal changes needed include: design GI integration for automatic design protection, mandatory GI registration in key international markets, community IP frameworks allowing collective ownership, and development of sui generis regimes that recognize cultural expressions as protected community rights.

What ethical responsibilities should international brands follow?

Ethical brands should collaborate with artisan cooperatives, adopt fair trade certifications, share credit and profits when borrowing from traditional designs, and engage in meaningful partnerships rather than mere appropriation of cultural elements.

Can traditional artisans take legal action against international brands?

While theoretically possible, practical challenges include limited financial resources, lack of legal expertise, absence of extraterritorial protection, and the high cost of international litigation, making it extremely difficult for artisan cooperatives to pursue legal action against global fashion houses.

What role can trade agreements play in protecting GI products?

Trade agreements like the India-EU Free Trade Agreement can include GI protection clauses that provide reciprocal protection in international markets, potentially allowing Indian artisans to enjoy legal safeguards in European markets and vice versa.

What was the outcome of the Bombay High Court case regarding Prada?

The Bombay High Court dismissed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) challenging Prada’s design, stating that only registered GI holders (LIDCOM and LIDKAR) have the legal standing to initiate civil proceedings for GI infringement, not third parties.

How many GI tags does India have?

As of 2024, India has over 643 registered Geographical Indication tags covering various categories including agricultural products, handicrafts, manufactured goods, and natural products across different states.

What was India’s first GI-tagged product?

Darjeeling Tea from West Bengal was India’s first product to receive GI tag protection in 2004, setting the precedent for protecting regionally specific products.

Can GI tags be registered as trademarks?

No, GI tags cannot be registered as trademarks because they represent collective community rights rather than individual or corporate rights. They serve different purposes under intellectual property law.

What happens if a GI tag expires?

If a GI tag is not renewed within the grace period of six months after expiry, the registration is permanently deleted from the GI register. Anyone can then use the tag, and re-registration requires a completely new application process.

How does social media impact cultural appropriation cases?

Social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok have become powerful tools for calling out cultural appropriation, organizing boycotts, and raising awareness. Hashtags like #culturalappropriation often trend during major controversies, giving marginalized communities a platform to voice concerns.

What is the difference between inspiration and appropriation in fashion?

Inspiration becomes appropriation when designers copy traditional elements without acknowledgment, understanding, respect, or collaboration with the originating communities. Ethical inspiration involves proper attribution, cultural understanding, and often profit-sharing or collaborative partnerships.

Which states in India have the most GI tags?

Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu lead with the highest number of GI tags, reflecting their rich cultural heritage and diverse traditional products.

What government support exists for GI registration?

The Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) provides financial support for GI registration under the National Handicrafts Development Programme (NHDP). The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development also assists producer associations with registration and financing.

How do international conventions protect GI products?

International frameworks like the Paris Convention (1883), Lisbon Agreement (1958), and TRIPS Agreement provide multilateral protection for geographical indications, though enforcement remains challenging across borders.

Also Read: